Memento Mori

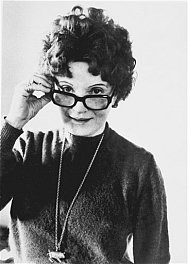

Muriel Spark

Book Club July 9, 2023

The Scottish novelist Muriel Spark converted to Catholicism as an adult and credited her new religion with enabling her to become a successful writer. But in Memento Mori, she shows no evidence of interest in such things as grace or redemption for her characters. The novel’s main characters are senior citizens, most of them dealing with their last days of physical and mental soundness; yet Spark seems to write gleefully of them as ninnies and neurotics – wasting their time running about trying to get the most of the time they have left when they could be doing the decent thing and simply disappearing from public life into the variety of care homes and hospices waiting for them.

The only character she shows evident sympathy for is the wickedest of them, the bully and crook in her early senior phase who does her best to corral and exploit the other elders in her grasp. Spark here reminds me of what Blake said of John Milton, the intensely religious author of Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained: “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God and at liberty when of Devils & Hell is because he was… of the Devil’s party without knowing it.”1

The main characters are being harassed by an anonymous serial phone caller, who simply says “Remember you must die” to his targets. That and the title suggest that the theme of the novel is that life needs to be put into perspective by keeping awareness of death’s inevitability close. There are also suggestions that there is honor in memorializing the dead: Alec Warner and Jean Taylor, former lovers, muse about the ephemerality of existence:

“Do you think, Jean, that other people exist?… you see that here is a

respectable question. Given that you believe in your own existence as

self-evident, do you believe in that of others? Tell me, Jean, do

you believe that I for instance, at this moment, exist?”

“…One does sometimes wonder, perhaps only half-consciously, if

other people are real.”

“Please,” he said, “wonder more than half-consciously about this question.

Wonder about it with as much consciousness as you have, and tell me what

is your answer.”

“Oh,” she said, “I think in that case, other people do exist. That’s my

answer. It’s only common sense… This graveyard is a kind of evidence,” she

said, “that other people exist.”

“…They are, I quite see, they are,” he said, “an indication of the

existence of others, for there are the names and times carved in stone.

Not a proof, but at least a large testimony.”

“…But the graves are at least reassuring,” she said, “for why bother to

bury people if they don’t exist?”

Their conversation suggests a literary project of anchoring the existence of us the living, in this modern age, via acknowledgement of the dead and those near death; the novel thus becoming something of an embodiment of the title, a first draft of a eulogy. But later the narrative turns to suggest that acknowledging death means the undoing of life and certainty, rather than the culmination and crowning of them. Later, after Jean has retired to a nursing home, she says to Alec:

We all appear to ourselves frustrated in our old age, Alec, because we cling to everything so much. But in reality we are still [in retirement] fulfilling our lives.

But in her case as in most of the others, the fulfillment seems to come from giving up, from letting go of one’s life’s goals and giving in to the uncertainties of meaning and existence, embodied in the uncertainty about the nature of the phone stalker. Sparks’ sympathies go to the characters who retire and disappear, and directs mockery to those who continue to try living a full life.

The exception, and the turn of narrative purpose, comes in depiction of the antics of Mrs. Pettigrew, the live-in caretaker who browbeats her elderly charges into docility for her own convenience, engages in power struggles against other servants who might challenge her will, and snoops her way into blackmail opportunities. Her verve, energy and clarity of purpose distinguish her from the other characters, and she is the only one fruitfully in command of her life’s direction.

The unveiling of Sparks’ true attitude and agenda in her delight with Mrs. Pettigrew suggests another commentary on Milton: “was Milton trying to tell us that being bad was more fun than being good?”2