Some Prefer Nettles

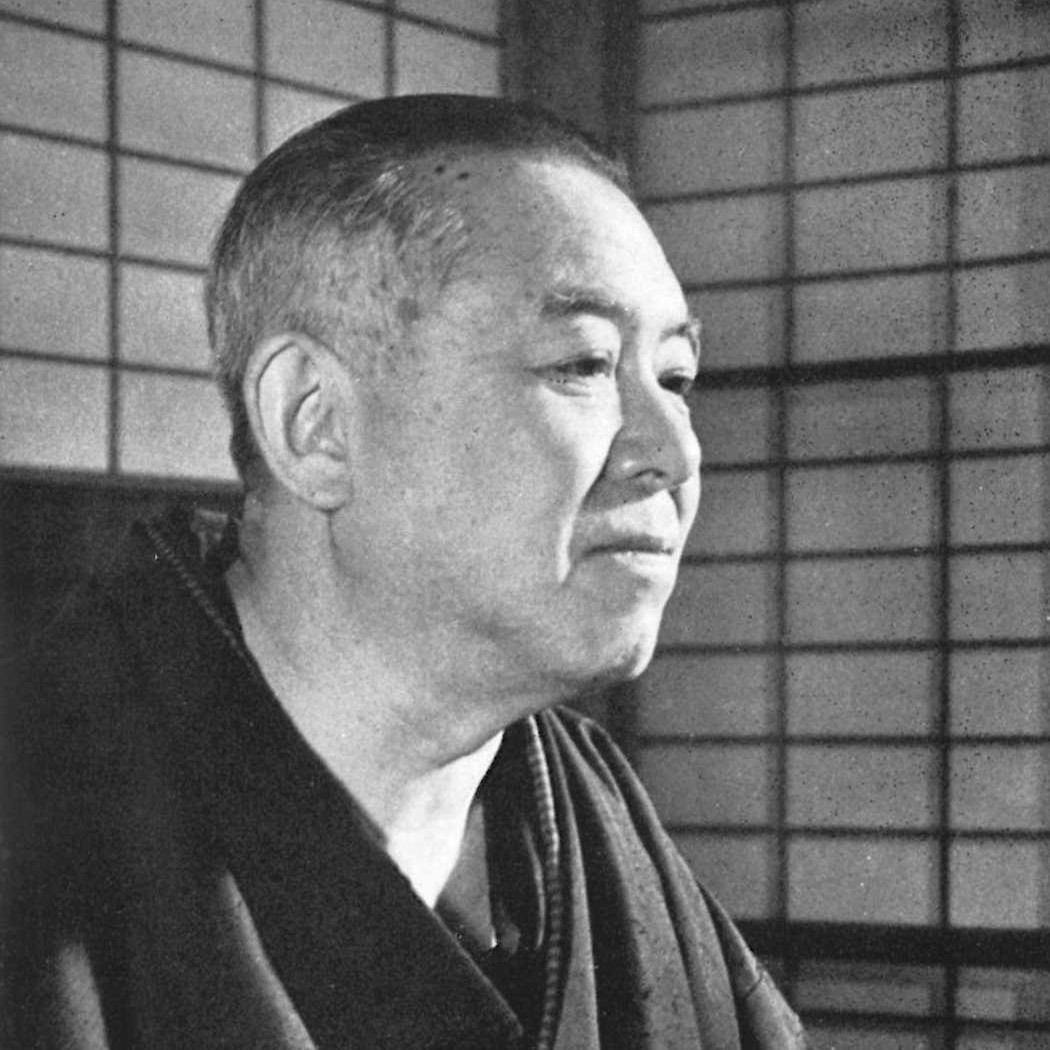

Junichiro Tankzaki

Book Club December 3, 2023

Some Prefer Nettles is a dry, arch domestic comedy with a hidden dark dimension, about an affluent married couple who have determined that their marriage is over, but can’t bring themselves to take the final step of seeking a divorce – each waiting on the other to make the decisive break. And so they carry on in a years-long exquisite expectant misery. Extended stasis is hardly something that a narrative can be crafted from, and the novel indeed upends any notions of a western-style progression of conflict, climax and resolution. But the work is so full of meticulously crafted observational ironies, that it is carried forward on the momentum of successive revelatory insights, carefully hidden from direct view but nevertheless breaking through the confusion of piled up puzzles and contradictions. It presents an alternative concept of the novel form, resembling the making of a color woodblock print: as each color ink is patiently applied to paper by a separate block, the total composition of the work eventually resolves itself.

The story takes place in and around Osaka, over the course of a spring season in the late 1920s, as the couple Kaname and Misako are drawn into her father’s retirement enthusiasm for classical Japanese puppet theater. This lead-off level of irony is easy to spot; as the couple endure the awkward social demands of attending performances together with her father (and waited on by the old man’s mistress O-hisa), it is clear that they are driven by the external imperatives of social convention, while the tragic romantic plots of the puppet plays invite comparison to the couple’s own situation.

On top of this, Kaname observes that his father-in-law has put great effort into training and shaping O-hisa, in her early twenties, to fit the role of the ideal hostess of the antique classical Japanese culture, just as it is being replaced by the country’s rapid Westernization ( “She’s one of the antiques in his collection, exactly like an old doll,” Kaname remarks to Misako). There’s no mistaking the identification of people with puppets and dolls. But…

Kaname slowly reveals his dark side in the way he is becoming consumed by his sensual obsessions. At first this side of him is presented in amusing fashion, as he fantasizes being free of his wife and reliving the pleasures of his youth with fresher women. Before long his cousin delivers to him an expensive Western volume he has requested from a specialty bookseller, an edition of 1001 Arabian Nights with lavish erotic illustrations which he flips through languorously but with intent notice of the charms of women of another race. Later, free from Misako for a day, he visits his favorite prostitute Louise in a brothel that specializes in offering white women. But Louise has some Asian blood and worries that her complexion is too dark, so she covers herself in white cosmetic powder to lighten herself. Kaname finds that after their rendezvous much of the powder has adhered to him.

This calls back to an earlier erudite discussion of the fine points of puppet artistry, which includes the comment, “The Osaka craftsmen, in their efforts to produce the effect of the human skin, leave a coating of powder over the paint.” Kaname is first figuratively, then literally identified with a puppet or doll, captured in transition to something refined but monstrous. After encountering Louise, the scent of her powder “seemed to sink deep into his skin, it permeated his clothes, it even spread through the taxi when he left and overwhelmed the room when he got home.”

Thus all Kaname’s comparisons of O-hisa to a doll directed by his father-in-law become twisted up in irony. He himself is transforming into something of an automaton, driven only by yearnings, lusts and social expectations, but with no inner life. It is a depiction of a modernist form of the ancient Buddhist concept of samsara.

O-hisa, by contrast, gradually embodies a striking form of liberation. Although by no means free in the role put upon her as servant/mistress, she acquires an archetypal power as she comes to embody the meeting of the present and past, rather than simply cosplaying it as her master intends.

Again, this is depicted at first in subtle, wry fashion. Although not particularly attractive herself, her name is shared by a well-known classic beauty of the eighteenth century, who was depicted many times in the woodblock prints of her era. Early on, Kaname remarks on her unappealing dentition: “her two front teeth were as black at the roots as if they had been stained in the old court manner….” But as he himself notes, stained black teeth were fine ladies’ court fashion for centuries in classical Japan. In her present poverty and lack of dental hygiene, she effortlessly echoes the most refined details of the former era.

Kaname notices that she and his father-in-law have unexpectedly achieved a degree of intimacy, they have a free and easy discourse, he asks her advice and follows her instructions. He deeply envies this aspect of their association which is lacking in his own marriage.

Much later, Kaname visits a remote rural town said to be the birthplace of the puppet theater, accompanying his father-in-law and O-hisa, and the sight of her there drives him into a sort of reverie:

Kaname felt a deep repose come over him. “These old houses are so dark you have no idea what’s inside.”

Kaname thought of the faces of the ancients in the dusk behind their shop curtains. Here on this street people with faces like theater dolls must have passed lives like stage lives. The world of the plays – of O-yumi, Jurobei of Awa, the pilgrim O-tsuru, and the rest – must have been just such a town as this. And wasn’t O-hisa a part of it? Fifty years ago, a hundred years ago, a woman like her, dressed in the same kimono, was perhaps going down this same street in the spring sun, lunch in hand, on her way to the theater beyond the river. Or perhaps, behind one of these latticed fronts, she was playing “Snow” on her koto. O-hisa was a shade left behind by another age.

This collapse of space and time, of reality and metaphor, represents something of a last chance for Kaname, a koan of incommensurates, an opportunity for a modern analog of enlightenment, a recognition of the futility of putting his energy into the pursuits of sensual pleasures, which comes at the cost of failing to develop a spiritual identity, a psyche.

In The Taming of the Shrew, Kate says to her father who is trying to to foist her on eligible men in marriage, “I pray you, sir, is it your will to make a stale of me amongst these mates?”; a stale being a prop, an effigy, a lure. On some level she understands that the chief threat that marriage presents to her is not being shackled to a man, but to convention; to be a static part of the background behind active players, to give up her inner life and identity.

O-hisa faces a similar challenge and has made headway against it. After Kaname says goodbye to her and his father-in-law after their rural theater excursion, he sees them depart for a tour of Buddhist temples and tries to comfort himself again by imagining her as a doll whose only purpose is to please her master. But his unbidden reveries betray him:

The pious Buddhist aphorism written in large characters on the sections of O-hisa’s sun-shade (part of her pilgrim’s equipment) gradually faded away: “For the benighted the illusions of the world. For the enlightened the knowledge that all is vanity. In the beginning there was no east and west. Where then is there a north and south?” It seemed to him, as he watched them there on the dock with their sunshades in the growing distance, that between the two of them there was indeed “no east and west” in spite of the thirty years’ difference in their ages

O-hisa exhibits an uncanny form of power. Her role suggests the aesthetic concept of wabi, the flaw or contradiction in the work that indicates its limitations and points the way out of abstraction into the frame of reality. Although not free, she retains her humanity, her identity, her capacity for discourse, and a modernist ability to make the old new. Like Kate at the end of Shrew, her horizons are for the moment unbounded despite the paradoxes of her situation – suggesting a new age equivalent to nirvana.

The threads of irony come together at the end of the novel in disturbing, though still oblique, fashion. Kaname and Misako have at last let her father-in-law know of the possibility of their divorce, and the old man has invited them to his traditional Japanese home to talk it out, eventually taking Misako out to dinner to try to talk sense to her one-on-one. Kaname is left behind to be tended by O-hisa. At this point his last chance for spiritual self-awareness has passed, and he is at the mercy of events. O-hisa offers him a bath in their dark traditional bathroom, which he takes in their uncomfortable traditional tub, sitting glumly in fetid water, unchanged for days according to tradition. In contrast to O-hisa, he is cloistered in by the materiality of the old.

She ushers him to his room to stay the night. He again tries to comfort himself by objectifying O-hisa in his mind. Sitting alone in the dark room, he suddenly thinks he sees O-hisa in the corner – but it is just an antique puppet the old man has bought as a souvenir.

The previous layerings of irony suggest that Kaname is however mistaken in who he mistook the puppet for. The puppet is now fully a reflection of him. The novel suddenly ends when O-hisa enters the room with reading material and redirects Kaname’s attention away from the puppet to her. No suggestion is given as to what is to happen next. But…

The reader is fortunate that Tanizaki’s wicked wit provides keys to how to approach his ironies. Earlier in the text, while Kaname is still in the phase of bemused observation of his father-in-law’s enthusiasms, the old man asks Kaname’s opinion of an ancient folk song they have just heard:

“Did you understand the words, Kaname?…”

“I have the feeling that I understand vaguely, but I’d probably come up

with something wild if I tried to go at it grammatically.”

“Quite true… . The composers didn’t think about grammar. If you see

generally what was in their hearts, that’s really enough. The vagueness is

rich in its own way… that first part is about a man who visits a woman

secretly at night. Instead of anything direct we have the moon stealing in

through the window. And isn’t it better really to leave things only

hinted at?”

The title itself is a sort of key. It is derived from a Japanese proverb corresponding roughly to the English “one man’s poison is another man’s meat.” But upon what meat precisely do Kaname and Miyako feed? The experiences of the novel are not a pleasure for them, not a fulfillment of alternative preferences; they are not iconoclasts or rebels. They are not nourished, they are miserable.

An ironic reflection is required to complete the meaning of the title. The ironic reading is closer to another proverb in English: “As a dog returns to his own vomit, so a fool repeats his folly.” Some gorge on poison, knowing what it is they do. Samsara.

After the layerings of Kaname’s cruelty and lust that have been depicted over the course of the novel, his next move is easy to project, and thus the circle of dehumanizing obsessions is closed by irony in its purest form, that of total darkness. Kaname will try to seduce O-hisa away from his father-in-law, or to share her with him; and by stepping on this path he will enter Hell.