Myra Breckinridge

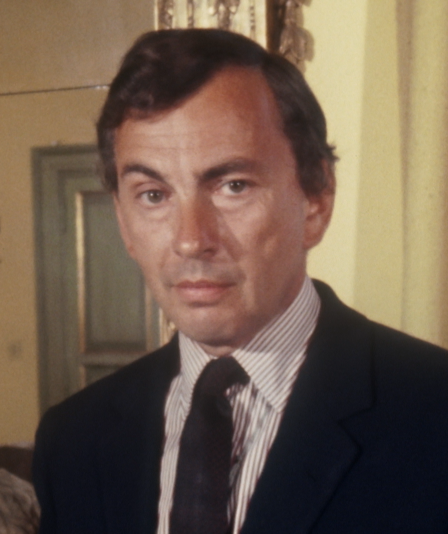

Gore Vidal

Book Club July 30, 2023

Myra Breckinridge is a modern warrior woman who has set herself on a quest for total fulfillment of all fantasies; chief of these being the total obliteration of traditional masculinity, thus turning humanity androgynous and averting the prospect of nuclear armageddon. She is subject and object of her heroic story, trying to save the world by saving herself.

The novel is the most unexpected and idiosyncratic of Gore Vidal’s novels. It is both an exemplary product of the late 1960’s and a cauldron of of the themes and obsessions that had filled his work from the beginning of his career.

In its anarchism, it undercuts and flips the table on every assertion, every expectation of the reader and every narrative breadcrumb trail laid down – to the extent that it’s difficult to envision how even to start talking about it, or how to end. Narrative summary? Themes? Character development? Social and political commentary? Ultimate meaning? The novel works to frustrate analysis or engagement from any angle.

It is a work of high literature that has the internal logic and structure of a cheap porn novel. Parts of the narrative are as contrived as the poolman arriving to find a young woman home alone in a skimpy bikini. I think that is because whenever a work undertakes to undermine and delegitimize all social conventions and mannerisms, even those of the rebels, nonconformists and freaks, choices of formal structure become limited – shortcuts have to be taken to get to the good parts. Be it a product of high or low culture the end result is often a horseshoe effect: a meeting in the middle, and the vulgar and refined wits become both targets and echoes of each other. For example when a narrative work busies itself with capturing total anarchy in the face of impending obliteration, it often turns out that there are only two acceptable choices for wrapping things up: breaking the frame (as in Naked Lunch, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, The Final Programme, The Bacchae, Blazing Saddles), or a contrapuntal reversion to conservative domesticity (A Clockwork Orange, Natural Born Killers, Deep Throat, Robert Heinlein’s Job, Candide). As it turns out, Myra Breckinridge opts for the latter. The author consequently risks disappointment or fury on the part of the reader… but really, what other choices were there?

It’s tempting to approach Myra as a work of self-examination and self-criticism on Vidal’s part. But I don’t think it should be necessary to reference the life of the artist to comprehend the artwork. On the other hand, with this work who knows what goes. Maybe Vidal simply considered himself one of the overblown contemporary mainstream idols to be knocked over.

Early along, Myra is clearly Vidal’s voice. In her erudition and love of films, particularly her adoration of film critic Parker Tyler, she echoes him. Her thoughts run to the sublime: “Tyler’s vision (films are the unconscious expressions of age-old human myths) is perhaps the only important critical insight this century has produced… Auden once wrote an entire poem praising limestone, unaware that any one of a thousand frames from Tarzan and the Amazons (1945) had not only anticipated him but made irrelevant his efforts.”

Later she embodies Vidal’s worldly cynicism: “what, finally, are human relations but the desire in each of us to exercise absolute power over others?”

And: “It is hate alone which inspires us to action and makes for civilization. Look at Juvenal, Pope, Billy Wilder.”

As the story progresses, she becomes tedious – in conversation with the young people she condescends to as if children, she starts to sound like the most annoying person in a college dorm lounge:

I was brilliant. I quoted the best of the world’s food authorities (famine for us all by 1974 and forget about plankton and seaweed: not enough of it). I demonstrated that essentially Malthus had been right, despite errors of calculation… What is to be done? How is the race to be saved…? My answer was simple enough: famine and war are now man’s only hope. To survive, human population must be drastically reduced. Happily, our leaders are working instinctively toward that end, and there is no doubt in my mind that nature intends Lyndon Johnson and Mao Tse-tung to be the agents of our salvation… If I say so myself, I had my listeners’ eyes bugging out by the time I had sketched for them man’s marvelous if fiery fate.

Vidal taking himself down a peg here? Self-satire? Acknowledging how tiresome his parlor-room polemics could be?

But as Myra’s thoughts and discourse become more convoluted and profane, she is falling in love with Mary-Ann, a beautiful young woman, and losing sight of her objective of destroying masculinity. Mary-Ann’s love draws Myra away from fantasies of disintegration and brings her back around to visions of wholeness, here:

Though I yearn romantically for the classic films of the Forties, I know that they can never be reproduced since their era is as gone as the Depression, World War II and the national innocence which made it possible for Pandro S. Berman and a host of others to decorate the screens of tens of thousands of movie theatres with perfect dreams. There was a wholeness then which is lacking now

and here:

there is something about Mary-Ann’s wholeness that excites me. There is a mystery to be plumbed, though whether or not it is in her or in myself or in us both I do not know.

Yet just as Myra and Mary-Ann’s love is about to reach a place of perfected satisfaction, wholeness proves to be a chimera. Myra is involved in a car accident; she is surgically undone and remade and learns to live with a new identity, her quest for rapture left behind. In its place is a new lifestyle in a different mode of incompleteness. But that is not a barrier to happiness; rather, in a broken world one may find that in one’s brokenness one is, as Sam Spade observed “in step with life.”

Is this the message and meaning of the novel? If so is it uplifting or a cop-out? If Myra is Vidal’s voice does the ending represent a life lesson accepted by Vidal himself?

Vidal was not one for embracing domesticity. Or rather, he oscillated for decades between a mutant form of domesticity in Italy, and part-time residence ensconced in the apocalyptic vistas of California amid the illusion and self-deception he despised. Does the record of his own restless and surreal life invalidate the apparent conclusion of the novel? Can any author be held so personally responsible for the integrity of one’s work?

I got a strange glimmer of insight from an unexpected source. The novel A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess is kin to Myra in its anarchic and apocalyptic vision. It also features an unexpected reversion to domesticity, infuriating to some readers. In its final chapter (cut from the film) the main character Alex decides to give up his life of gang violence, sex crimes, drugs and alcohol. He resolves instead to settle down, look for love, maybe even start a family. While imagining the eagerness with which he will be replaced in his gang hierarchy, he muses, “Power power, everybody like wants power.”

Alex’s observation mirrors those of Myra/Vidal. But even as Alex expresses it he is already transitioning away from this mindset and resolving to find something more in human relationships. Does the fact that Alex is making this statement at this time indicate not that he believes it, but is objectifying and othering the concept, thus suggesting that he is moving beyond it?

This contradiction in a spiritually related novel made me wonder if a similar dynamic was at work in Vidal, not so far-fetched a concept I think in a genre where denial is plenary and choices of formal approach are constrained. Was his well-practiced patter of cynical public statements concerning power, greed, empire, love, etc. not a rubric of his viewpoints (as he let his audiences assume), but an exercise in keeping himself from being entrapped by them, of defeating their neurotic power and maintaining his distance from them?

Either this, or Myra Breckinridge is a work of slippery cynicism, in which Vidal fits himself for a straitjacket and then wriggles out of it and disappears leaving the reader to wonder what happened.

Or perhaps what Vidal reveals is that he both believed his cynical assertions and didn’t believe them, just as he was a domesticated resident of Italy and also a participant in the dreamworld of his second home Los Angeles, as he was a man who said he didn’t understand love and was the creator of Myra whose life climaxed in eloquent praise of love’s glory and mystery.

The only way I could satisfy myself with reading this novel was to envision Vidal as a sort of modern Dionysian priest, empowered by his visionary authorial rituals to move between modes, to partake periodically in the madness of the gods yet not be ripped apart, given the divine grace to retreat into safe domesticity when the revels were ended. As such he acted as envoy and intermediary between worlds: able to receive visions and hear voices and then bring them back to his audience’s ken, untouched, but empty.